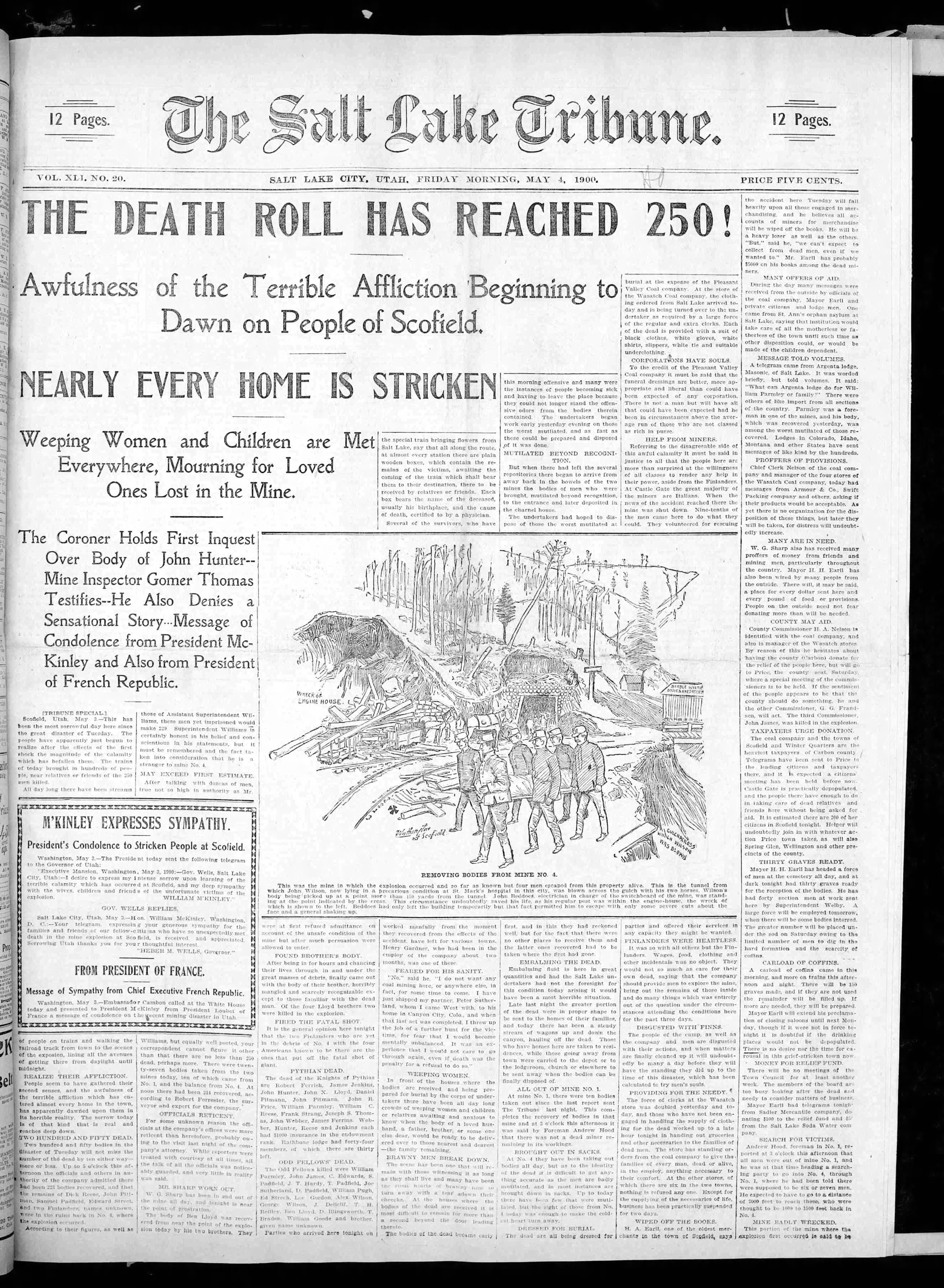

On 1 May 1900, Scofield, Utah became home to one of the deadliest mining disasters in United States history.

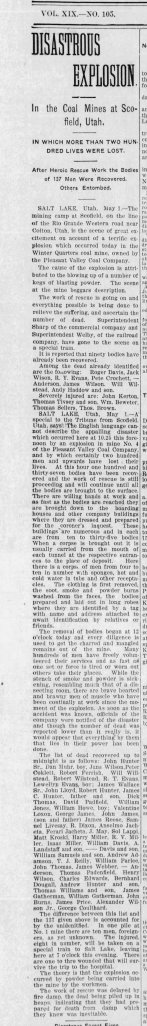

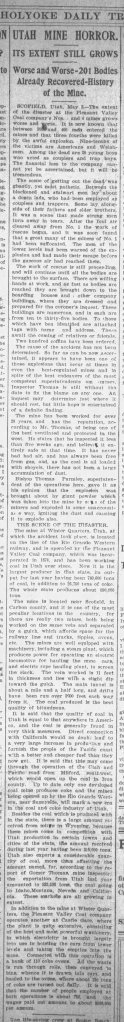

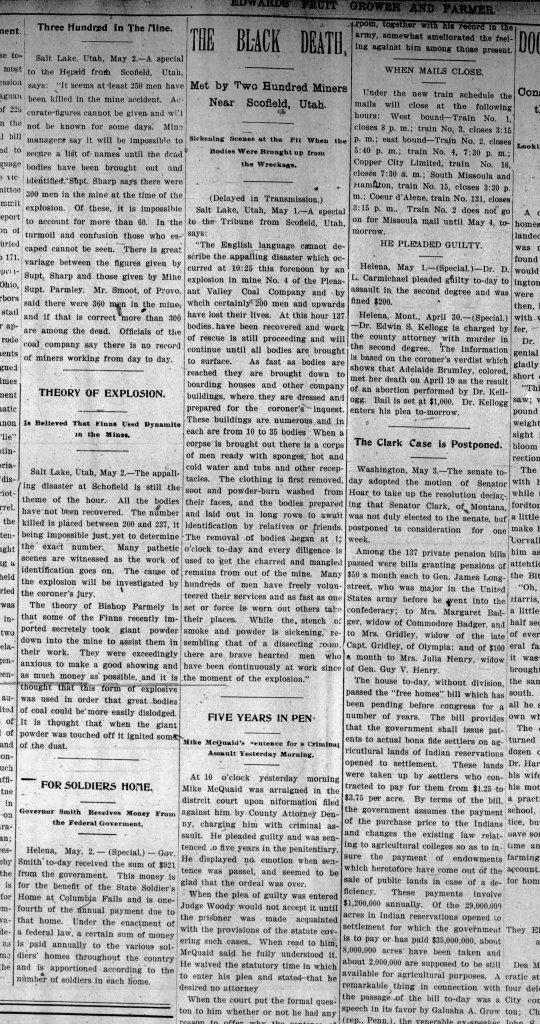

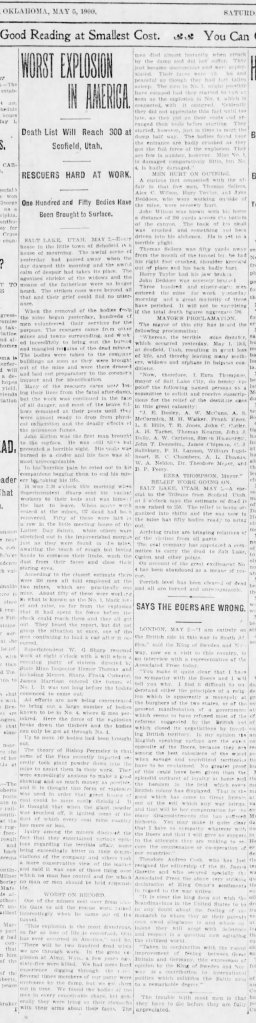

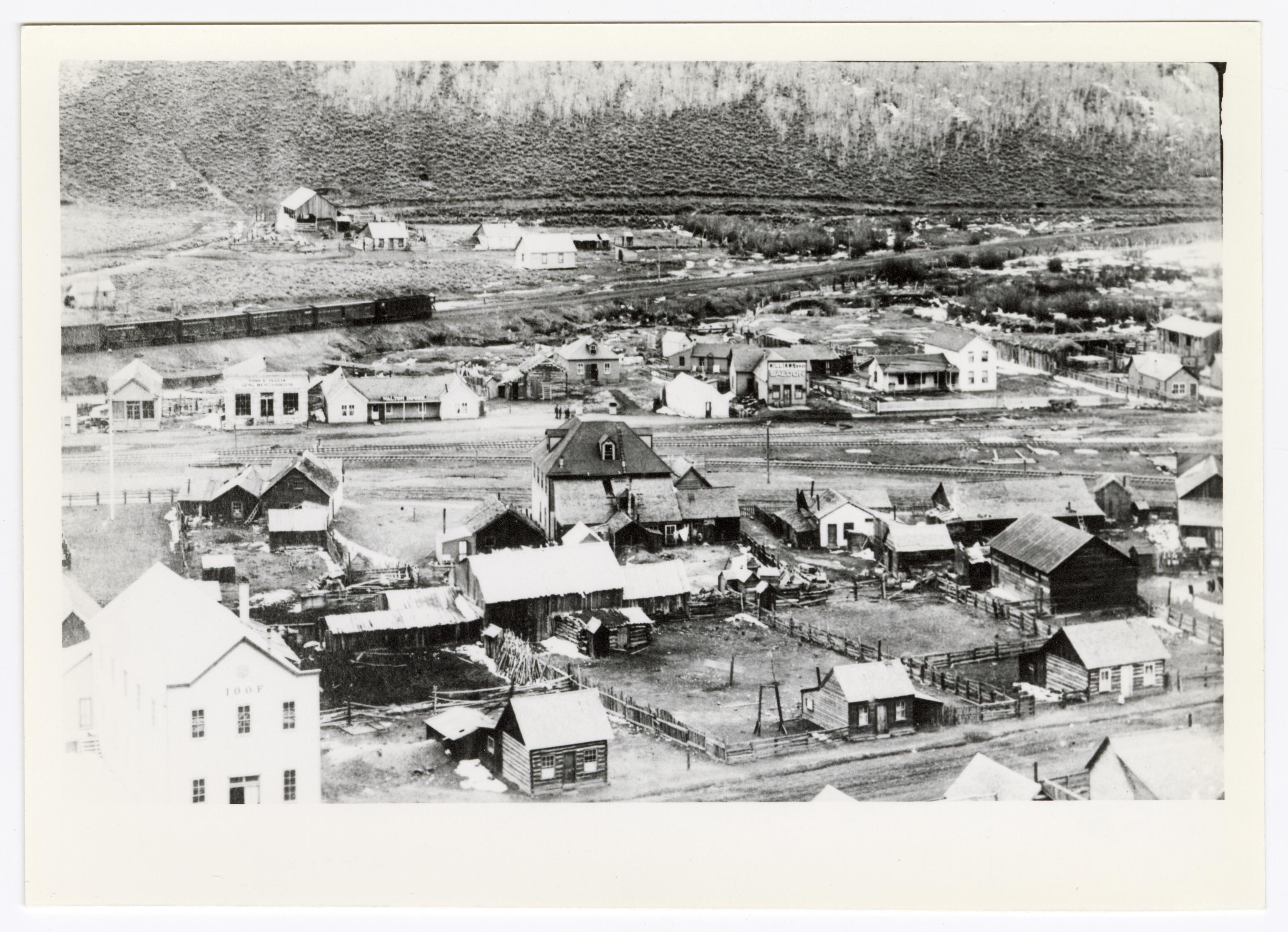

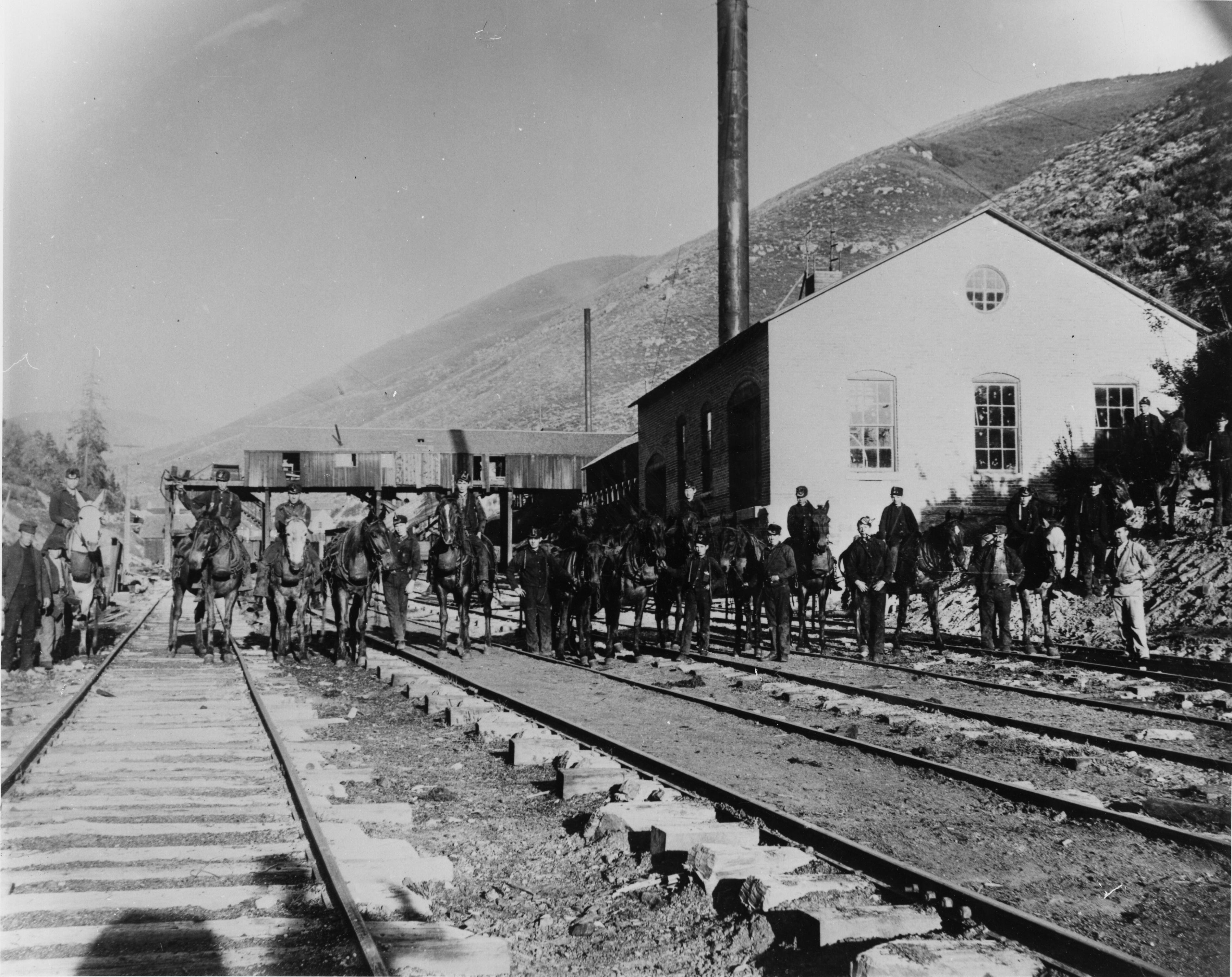

The day shift had just begun around 10:25, when an explosion occurred in Number 4 mine of Winter Quarters. Folks in neighboring towns thought the thunderous boom to be nothing more than a premature celebration of Dewey Day. They would soon find out the devastating origins. Winter Quarters coal mine, owned by Pleasant Valley Coal Company (acquired by Denver, Rio Grande & Western in 1882) was one of the safest in the world, or at least thats what miners who expressed concerns for their safety had been told.

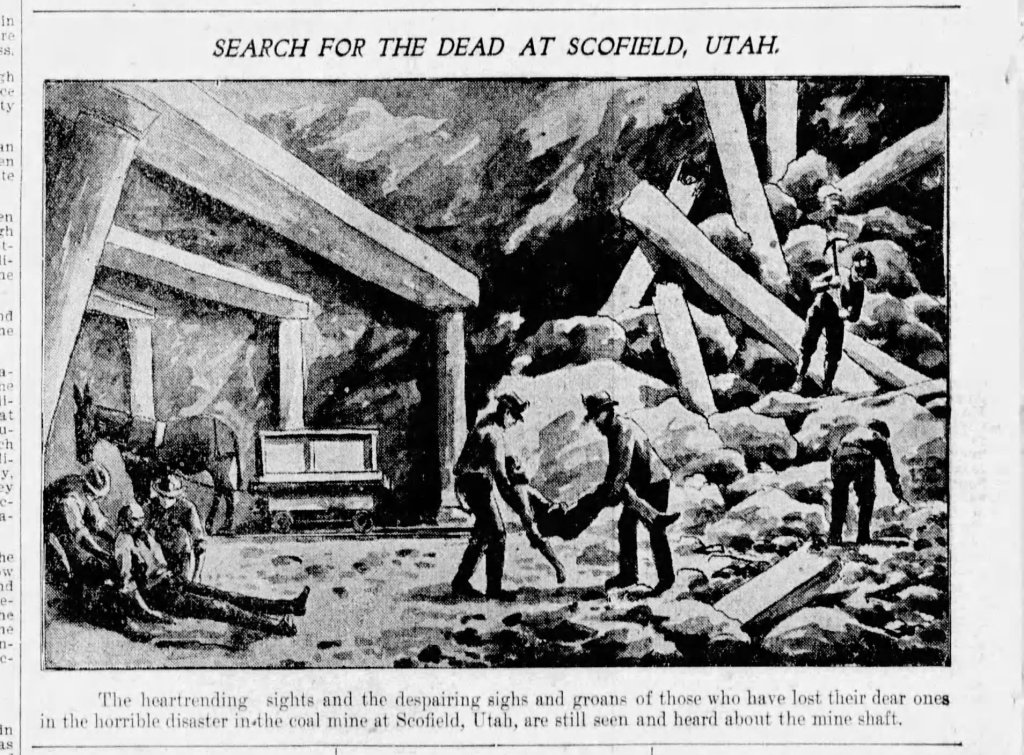

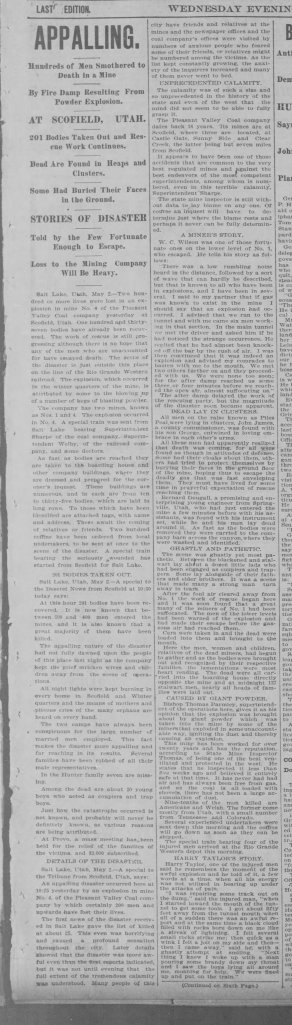

Above ground, miners sprang into action forming relief crews. Number 4 the newest addition was small with a depth of 1,600 feet (488 meters), it had 4 cross entries, and 26 rooms. The impact of the explosion caused debris to barricade the entrance, miners began to remove the heavy timber, mangled metal, and a dead horse, who’s mining companion had been hurled 820 feet (250 meters) away. They cleared the entrance within 20 minutes. Another crew, within minutes of the explosion had entered the mine through its connecting web of tunnels, encountering “after-damp” (a mix of noxious gasses), 2 members fell unconscious and had to be carried out.

Entombed in the tunnels were men seemingly frozen in time, relief crews reported: a father and son embracing each other in their last moments, another sitting down to his tobacco pipe in hand, and another eating a sandwich. They had been working in mine Number 1, where after the explosion they had made their way towards the shortest exit route, mine Number 4. They were met with deadly “after-damp”. The rescue attempts weren’t all futile, one miner was discovered still working in one of the rooms, blissfully unaware of the explosion.

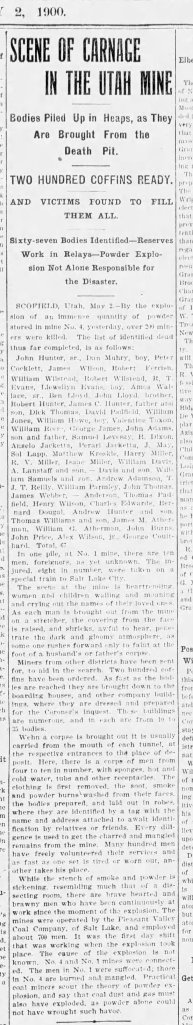

Bodies of the deceased were stacked into mine cars and sent up to the surface, where they were taken to the boarding house for identification. Those whom had been closest to the impact of the explosion, burned and mutilated, were brought up in sacks. Miners who survived, were sent by special railcar to St. Mark’s Hospital. On 2 May, 14 hours after the initial explosion, the exhausted crews ended their first day.

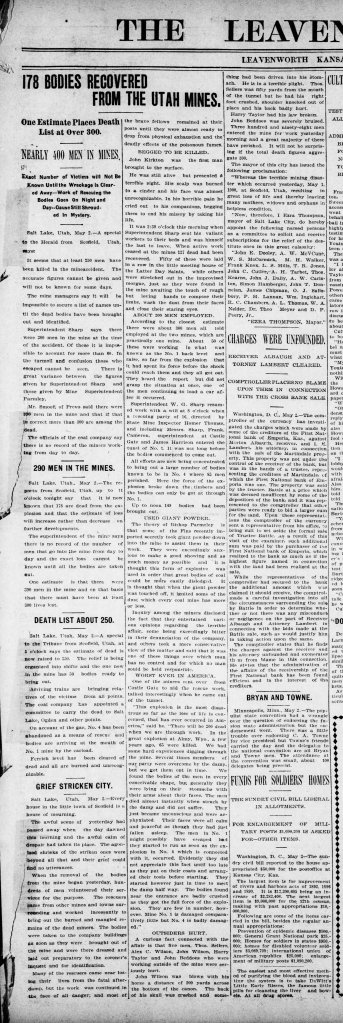

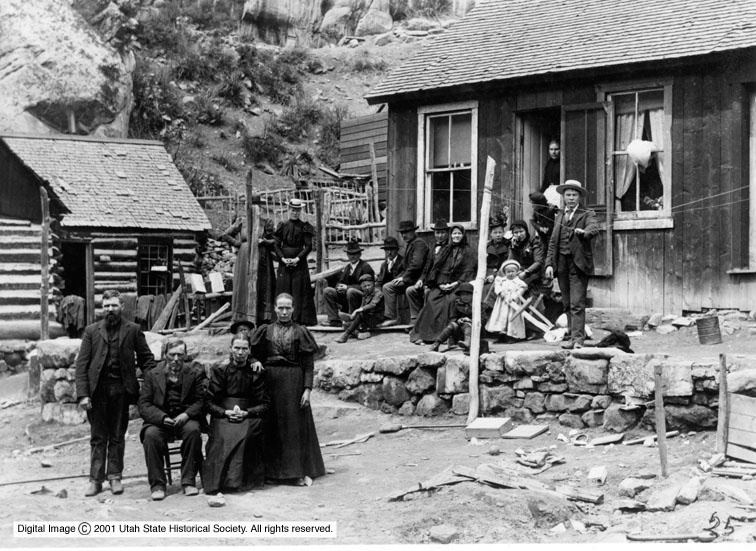

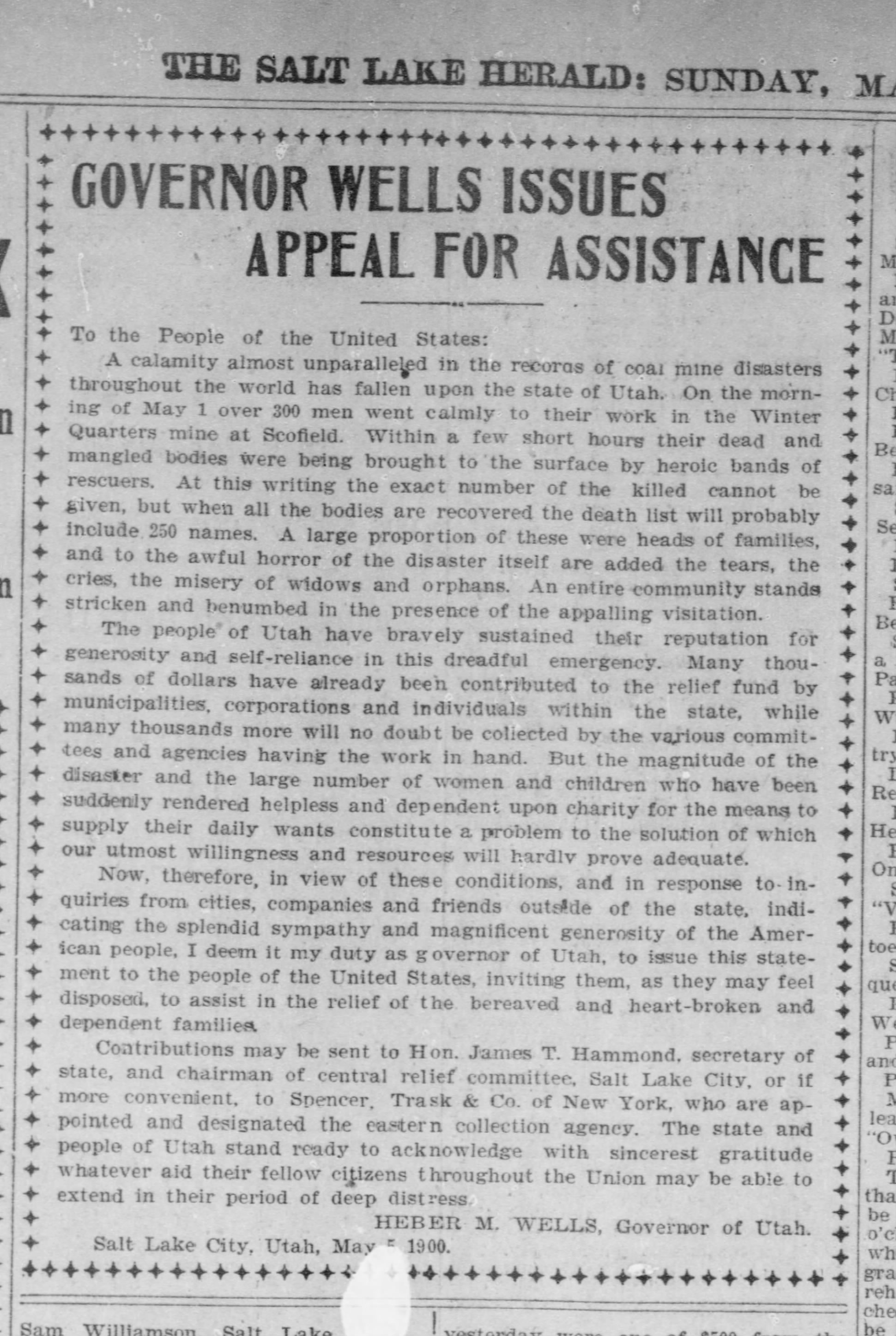

The news of the deadly event spread quickly. Miners from neighboring Carbon County coal mines arrived the next morning to provide support to those at Winter Quarters. Women from all around Utah, made their way to Winter Quarters to help the families and children who had been left fatherless. Scofield officials, worried they may not have enough workers to dig the graves, were relieved when 50 men from Provo volunteered. A special legislative session had been called, but the state representatives declined to provide any financial support. Working class people from cities and counties around the country, held fundraisers to support the survivors. The Pleasant Valley Coal Company provided funeral necessities for the miners to receive proper burials. 125 Coffins arrived from Salt Lake City, UT and 75 from Denver, CO.

On 5 May 125 miners were buried in the Scofield cemetery. Other bodies were sent home via railroad to their home counties to be buried. The official body count landed at 200, though some miners who had been stationed to count the decease coming out in the mining cars had counts as high as 246. The Finnish miners stated that they had 15 miners still unaccounted for. There was not a record of who had entered the mine that morning and the extensive mutilation of some, made it even harder to identify the dead.

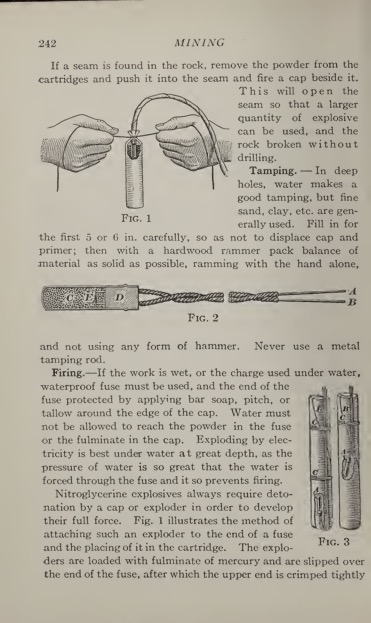

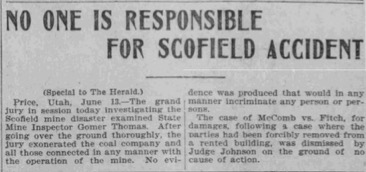

Ultimately, no one was held responsible for the disaster. The United States Bureau of Mines was unable to determine the exact cause of the explosion, however, they did note that it could’ve been prevented by removing dust, using water, and proper handling of explosives. Pleasant Valley Coal Company paid the surviving families $500, and full wages for the dead miners, while also forgiving the miners “debts” at the company store. On 28 May Winter Quarters mines, reopened.

Fuller, Craig. “Finns and the Winter Quarters Mine Disaster.” Utah Historical Quarterly LXX, no. 2 (2002): 123–39.

Taniguchi, Nancy J. “An Explosive Lesson.” Utah Historical Quarterly LXX, no. 2 (2002): 140–57.

Powell, Allan Kent. “Scofield Mine Disaster.” Utah History Encyclopedia, 2017. https://www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/s/SCOFIELD_MINE_DISASTER.shtml.

Powell, Allan Kent. “Labor at the Beginning of the 20th Century: The Carbon County, Utah Coal Fields, 1900 to 1905.” Thesis, University of Utah, 1972.

Tingey, Jack. “Coal Correspondence: Inspector Gomer Thomas and the 1900 Scofield Mine Disaster.” Utah State Archives and Records Service, May 1, 2023. https://archivesnews.utah.gov/2023/05/01/coal-correspondence-inspector-gomer-thomas-and-the-1900-scofield-mine-disaster/.

Watt, Ronald G. “Explosion of Pleasant Valley Coal Company,” History of Carbon County, May 3, 2016.

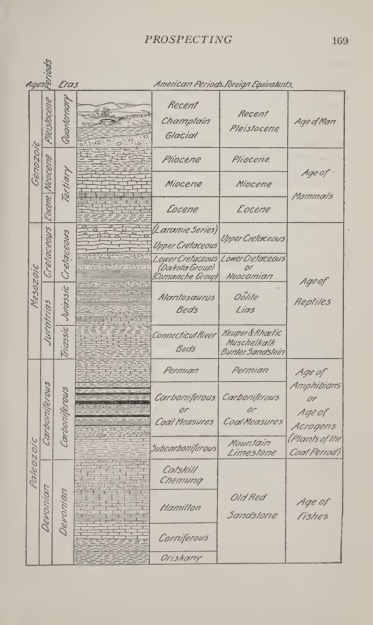

Excerpts from The Coal Miner’s Handbook